Strategies for engineered negligible senescence

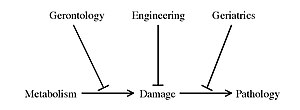

Strategies for engineered negligible senescence (SENS) is a range of proposed regenerative medical therapies, either planned or currently in development, for the periodic repair of all age-related damage to human tissue. These therapies have the ultimate aim of maintaining a state of negligible senescence in patients and postponing age-associated disease.[1] SENS was first defined by British biogerontologist Aubrey de Grey. Many mainstream scientists believe that it is a fringe theory.[2] De Grey later highlighted similarities and differences of SENS to subsequent categorization systems of the biology of aging, such as the highly influential Hallmarks of Aging published in 2013.[3][4]

While some biogerontologists support the SENS program, others contend that the ultimate goals of de Grey's programme are too speculative given the current state of technology.[5][6] The 31-member Research Advisory Board of de Grey's SENS Research Foundation have signed an endorsement of the plausibility of the SENS approach.[7]

Framework

[edit]

The term "negligible senescence" was first used in the early 1990s by professor Caleb Finch to describe organisms such as lobsters and hydras, which do not show symptoms of aging. The term "engineered negligible senescence" first appeared in print in Aubrey de Grey's 1999 book The Mitochondrial Free Radical Theory of Aging.[8] De Grey defined SENS as a "goal-directed rather than curiosity-driven"[9] approach to the science of aging, and "an effort to expand regenerative medicine into the territory of aging".[10]

The ultimate objective of SENS is the eventual elimination of age-related diseases and infirmity by repeatedly reducing the state of senescence in the organism. The SENS project consists in implementing a series of periodic medical interventions designed to repair, prevent or render irrelevant all the types of molecular and cellular damage that cause age-related pathology and degeneration, in order to avoid debilitation and death from age-related causes.[1]

Strategies

[edit]As described by SENS, the following table details major ailments and the program's proposed preventative strategies:[11]

| Issue | Proposed countermeasures |

|---|---|

| Extracellular aggregates | Immunotherapeutic clearance |

| Accumulation of senescent cells | Senescence marker-targeted toxins, immunotherapy |

| Extracellular matrix stiffening | AGE-breaking molecules, tissue engineering |

| Intracellular aggregates | Novel lysosomal hydrolases |

| Mitochondrial mutations | Allotopic expression of 13 proteins |

| Cancerous cells | Removal of telomere-lengthening machinery |

| Cell loss, tissue atrophy | Stem cells and tissue engineering |

Scientific reception

[edit]While some fields mentioned as branches of SENS are supported by the medical research community, e.g., stem cell research, anti-Alzheimers research and oncogenomics, the SENS programme as a whole has been a highly controversial proposal. Many of its critics argued in 2005 that the SENS agenda was fanciful and that the complicated biomedical phenomena involved in aging contain too many unknowns for SENS to be fully implementable in the foreseeable future.[12]

Cancer may deserve special attention as an aging-associated disease, but the SENS claim that nuclear DNA damage only matters for aging because of cancer has been challenged in other literature,[13] as well as by material studying the DNA damage theory of aging. More recently, biogerontologist Marios Kyriazis has criticised the clinical applicability of SENS[14][15] by claiming that such therapies, even if developed in the laboratory, would be practically unusable by the general public.[16] De Grey responded to one such criticism.[further explanation needed][17]

2005 EMBO Reports statement

[edit]In November 2005, 28 biogerontologists published a statement of criticism in EMBO Reports, "Science fact and the SENS agenda: what can we reasonably expect from ageing research?,"[12] arguing "each one of the specific proposals that comprise the SENS agenda is, at our present stage of ignorance, exceptionally optimistic,"[12] and that some of the specific proposals "will take decades of hard work [to be medically integrated], if [they] ever prove to be useful."[12] The researchers argue that while there is "a rationale for thinking that we might eventually learn how to postpone human illnesses to an important degree,"[12] increased basic research, rather than the goal-directed approach of SENS, is currently the scientifically appropriate goal.

Technology Review contest

[edit]In February 2005, the MIT Technology Review published an article by Sherwin Nuland, a Clinical Professor of Surgery at Yale University and the author of How We Die,[18] that drew a skeptical portrait of SENS, at the time de Grey was a computer associate in the Flybase Facility of the Department of Genetics at the University of Cambridge.[19] While Nuland praised de Grey's intellect and rhetoric, he criticized the SENS framework both for oversimplifying "enormously complex biological problems" and for promising relatively near-at-hand solutions to those unsolved problems.[19]

During June 2005, David Gobel, CEO and co-founder of the Methuselah Foundation with de Grey, offered Technology Review $20,000 to fund a prize competition to publicly clarify the viability of the SENS approach. In July 2005, Jason Pontin announced a $20,000 prize, funded 50/50 by Methuselah Foundation and MIT Technology Review. The contest was open to any molecular biologist, with a record of publication in biogerontology, who could prove that the alleged benefits of SENS were "so wrong that it is unworthy of learned debate."[20] Technology Review received five submissions to its challenge. In March 2006, Technology Review announced that it had chosen a panel of judges for the Challenge: Rodney Brooks, Anita Goel, Nathan Myhrvold, Vikram Sheel Kumar, and Craig Venter.[21] Three of the five submissions met the terms of the prize competition. They were published by Technology Review on June 9, 2006. On July 11, 2006, Technology Review published the results of the SENS Challenge.[22]

In the end, no one won the $20,000 prize. The judges felt that no submission met the criterion of the challenge and discredited SENS, although they unanimously agreed that one submission, by Preston Estep and his colleagues, was the most eloquent. Craig Venter succinctly expressed the prevailing opinion: "Estep et al. ... have not demonstrated that SENS is unworthy of discussion, but the proponents of SENS have not made a compelling case for it."[22] Summarizing the judges' deliberations, Pontin wrote in 2006 that SENS is "highly speculative" and that many of its proposals could not be reproduced with current scientific technology. Myhrvold described SENS as belonging to a kind of "antechamber of science" where they wait until technology and scientific knowledge advance to the point where it can be tested.[22][23] Estep and his coauthors challenged the result of the contest by saying both that the judges had ruled "outside their area of expertise" and had failed to consider de Grey's frequent misrepresentations of the scientific literature.[24]

SENS Research Foundation

[edit]The SENS Research Foundation is a non-profit organization co-founded by Michael Kope, Aubrey de Grey, Jeff Hall, Sarah Marr and Kevin Perrott, which is based in California, United States. Its activities include SENS-based research programs and public relations work for the acceptance of and interest in related research.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b de Grey, Aubrey; Rae, Michael (September 2007). Ending Aging: The Rejuvenation Breakthroughs that Could Reverse Human Aging in Our Lifetime. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, 416 pp. ISBN 0-312-36706-6.

- ^ Warner, H.; Anderson, J.; Austad, S.; Bergamini, E.; Bredesen, D.; Butler, R.; Carnes, B. A.; Clark, B. F. C.; Cristofalo, V.; Faulkner, J.; Guarente, L.; Harrison, D. E.; Kirkwood, T.; Lithgow, G.; Martin, G.; Masoro, E.; Melov, S.; Miller, R. A.; Olshansky, S. J.; Partridge, L.; Pereira-Smith, O.; Perls, T.; Richardson, A.; Smith, J.; Von Zglinicki, T.; Wang, E.; Wei, J. Y.; Williams, T. F. (Nov 2005). "Science fact and the SENS agenda. What can we reasonably expect from ageing research?". EMBO Reports. 6 (11): 1006–1008. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400555. ISSN 1469-221X. PMC 1371037. PMID 16264422.

- ^ De Grey, Aubrey D.N.J. (2023). "The Divide-and-Conquer Approach to Delaying Age-Related Functional Decline: Where Are We Now?". Rejuvenation Research. 26 (6): 217–220. doi:10.1089/rej.2023.0057. PMID 37950714. S2CID 265127778.

- ^ "The Hallmarks of Aging: Cell".

- ^ Warner H; Anderson J; Austad S; et al. (November 2005). "Science fact and the SENS agenda. What can we reasonably expect from ageing research?". EMBO Reports. 6 (11): 1006–8. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400555. PMC 1371037. PMID 16264422.

- ^ Holliday R (April 2009). "The extreme arrogance of anti-aging medicine". Biogerontology. 10 (2): 223–8. doi:10.1007/s10522-008-9170-6. PMID 18726707. S2CID 764136.

- ^ "Research Advisory Board". sens.org. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ de Grey, Aubrey (November 2003). The Mitochondrial Free Radical Theory of Aging. Austin, Texas: Landes Bioscience. ISBN 1-58706-155-4.

- ^ Bulkes, Nyssa (March 6, 2006). "Anti-aging research breakthroughs may add up to 25 years to life Archived 2020-04-02 at the Wayback Machine". The Northern Star. Northern Illinois University (DeKalb, USA).

- ^ . "Age-Related Diseases: Medicine's Final Adversary?". Huffington Post Healthy Living.

- ^ "Intro to SENS Research". SENS Research Foundation. Retrieved 2020-08-18.

- ^ a b c d e Warner; et al. (2005). "Science fact and the SENS agenda. What can we reasonably expect from ageing research?". EMBO Reports. 6 (11): 1006–1008. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400555. PMC 1371037. PMID 16264422.

- ^ Best, BP (2009). "Nuclear DNA damage as a direct cause of aging" (PDF). Rejuvenation Research. 12 (3): 199–208. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.318.738. doi:10.1089/rej.2009.0847. PMID 19594328.

- ^ Kyriazis M (2014). "The impracticality of biomedical rejuvenation therapies: translational and pharmacological barriers". Rejuvenation Research. 17 (4): 390–6. doi:10.1089/rej.2014.1588. PMC 4142774. PMID 25072550.

- ^ Kyriazis, Marios (2015). "Translating laboratory anti-aging biotechnology into applied clinical practice: Problems and obstacles". World Journal of Translational Medicine. 4 (2): 51–4. doi:10.5528/wjtm.v4.i2.51.

- ^ Kyriazis M, Apostolides A (2015). "The Fallacy of the Longevity Elixir: Negligible Senescence May be Achieved, but Not by Using Something Physical". Current Aging Science. 8 (3): 227–34. doi:10.2174/1874609808666150702095803. PMID 26135528.

- ^ de Grey AD (2014). "The practicality or otherwise of biomedical rejuvenation therapies: a response to Kyriazis". Rejuvenation Research. 17 (4): 397–400. doi:10.1089/rej.2014.1599. PMID 25072964.

- ^ Nuland, Sherwin (1994). How We Die: Reflections on Life's Final Chapter. New York: Knopf Random House. ISBN 0-679-41461-4.

- ^ a b Nuland, Sherwin (1 February 2005). "Do You Want to Live Forever?". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Pontin, Jason (July 28, 2005). "The SENS Challenge Archived 2012-03-16 at the Wayback Machine". Technology Review.

- ^ Pontin, Jason (March 14, 2006). "We've picked the judges for our biogerontology prize Archived 2012-03-16 at the Wayback Machine". Technology Review.

- ^ a b c Pontin, Jason (July 11, 2006). "Is Defeating Aging Only A Dream? Archived 2020-04-02 at the Wayback Machine". Technology Review.

- ^ Garreau, Joel (October 31, 2007). "Invincible Man". Washington Post.

- ^ Estep, Preston W. (11 July 2006). "Preston Estep et al. Dissent". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Fishman, Jennifer R.; Settersten, Richard A. Jr.; Flatt, Michael A. (February 2010). "In the vanguard of biomedicine? The curious and contradictory case of anti-ageing medicine". Sociology of Health & Illness. 32 (2): 197–210. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01212.x. PMC 3414193. PMID 20003037.

- Isaacson, Betsy (5 March 2015). "Silicon Valley Is Trying to Make Humans Immortal—and Finding Some Success". Newsweek. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- Mykytyn, Courtney Everts (February 2010). "A history of the future: The emergence of contemporary anti-ageing medicine". Sociology of Health & Illness. 32 (2): 181–196. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01217.x. PMID 20149152.

- Olshansky, S. Jay; Carnes, Bruce A. (2013). "Science Fact versus SENS Foreseeable". Gerontology. 59 (2): 190–192. doi:10.1159/000342959. PMID 23037994. S2CID 207588602.