Lone Star (1996 film)

| Lone Star | |

|---|---|

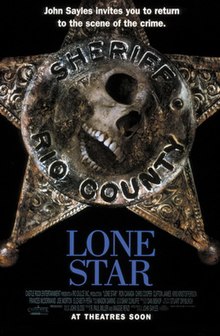

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Sayles |

| Written by | John Sayles |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Stuart Dryburgh |

| Edited by | John Sayles |

| Music by | Mason Daring |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Sony Pictures Classics |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 135 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3–5 million[1][2] |

| Box office | $13 million[2] |

Lone Star[3] is a 1996 American neo-Western mystery film written, edited, and directed by John Sayles and set in a small town in South Texas. The ensemble cast features Chris Cooper, Kris Kristofferson, Elizabeth Peña and Matthew McConaughey and deals with a sheriff's investigation into the murder of one of his predecessors. Filmed on location along the Rio Grande in southern and southwestern Texas, the film received critical acclaim, with critics regarding it as a high point of 1990s independent cinema as well as one of Sayles' best films. It was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, and also appeared on the ballot for the AFI's 10 Top 10 in the Western category.

Plot[edit]

Two off-duty sergeants from the base discover a human skeleton on an old U.S. Army rifle shooting range along with a Masonic ring, a Rio County sheriff's badge, and, later, an expended .45 pistol bullet. Sam Deeds, sheriff of Frontera, Texas, begins an investigation. Texas Ranger Ben Wetzel agrees with Sam that forensics backs up the identity of the skeleton as Charlie Wade, the infamously corrupt and cruel sheriff who preceded Buddy Deeds. Wade mysteriously disappeared in 1957, along with $10,000 in county funds. Buddy Deeds' big reputation and election as Sheriff resulted from his being widely believed to have confronted the despised Charlie Wade on his corruption and driven him from town.

Frontera is a border town with racial strife among the Tejano, African American, Native American, and Anglo populations, where the Anglo population is no longer the majority. Sam holds that office because he is the son of recently deceased legendary Sheriff Buddy Deeds. As a teenager Sam hated and rebelled against his tyrannical father, leaving town as soon as he was old enough. Since his return to the town two years prior, Sam has chafed under constant comparison to the inflated reputation of the beloved Buddy Deeds.

The town is enlarging and renaming the local courthouse in Buddy's honor and proposing the building of an unneeded new prison. Sam is skeptical about the use of Buddy Deed's name by local business leaders, such as Mercedes Cruz and Buddy's former chief deputy, Mayor Hollis Pogue, to promote projects for personal profit using taxpayers' money. As a teenager, Sam had been in love with Mercedes's Tejano daughter, Pilar, but the passionate relationship was strongly opposed by both Buddy and Mercedes, who took steps to separate them.

After a chance meeting in the present, the divorced Sam and the widowed Pilar, now a local teacher, begin to rekindle their lingering passion, again with staunch opposition from Mercedes who Pilar mistakenly believes objects to Sam because he is white.

Colonel Delmore Payne has returned to town as the commander of the local U.S. Army base. Son of Otis "Big O" Payne, a local nightclub owner and leader of the Black community, Delmore has been estranged from his father since childhood, when the serial womanizer abandoned Delmore and his mother. When a quarrel involving a soldier from the base results in a shooting death at Otis's club—witnessed by the colonel's own resentful underage son who is surreptitiously at the club to scout out his grandfather—Colonel Payne confronts Otis and threatens to make his establishment "off-limits." Otis counters that his establishment is the only place in town where Black soldiers are welcome.

Sam has always doubted the "official story" of Wade's disappearance. Despite being warned by Mayor Hollis Pogue and prominent local figures not to poke into events 30 years ago, Sam doggedly investigates the events leading up to Wade's murder. Wade terrorized the local Black and Mexican communities, extorting money from business owners and committing murders by setting up his victims and shooting them for "resisting arrest". In front of Deputy Hollis Pogue, Sheriff Wade murdered Eladio Cruz, Mercedes' husband, who was running a migrant smuggling operation across the border without kickbacks to Wade.

Uncovering secrets about his father's nearly 30-year term as sheriff, Sam discovers Buddy's own corruption, kickbacks, and use of prison labor for personal building projects. Buddy forcibly evicted residents of a small community to make a lake, with Buddy and Hollis receiving lakefront property. Going through old boxes of Buddy's papers, Sam discovers love letters from Buddy's longtime mistress—Mercedes Cruz.

Sam confronts Hollis and Otis about Wade's murder. Upon discovering Otis's clandestine gambling operation at the nightclub, a furious Wade ordered Otis to hand over extortion money. Wade was about to use his "resisting arrest" setup to kill Otis. Buddy Deeds arrived just as Hollis shot Wade to prevent Otis's murder. The three buried the body and took $10,000 from the county as an alibi for Wade's "abscondence". They gave the money to Mercedes—who was destitute after Wade killed Eladio—to buy her restaurant. Buddy and Mercedes later got involved. Sam decides to drop the issue, saying Wade's murder will remain unsolved. Hollis is concerned that people will assume Buddy killed Wade to take his job. Sam replies, "Buddy's a goddam legend; he can handle it."

Showing Pilar an old photo of Buddy embracing Mercedes, Sam tells her Eladio died 18 months before she was born, revealing Buddy is Pilar's father. Both are appalled over the years of deception and repercussions, but since Pilar cannot have any more children, they decide to continue their romantic relationship, despite the knowledge that they are half-siblings.

Cast[edit]

- Chris Cooper as Sam Deeds

- Tay Strathairn as young Sam

- Elizabeth Peña as Pilar

- Vanessa Martinez as young Pilar

- Kris Kristofferson as Charlie Wade

- Matthew McConaughey as Buddy Deeds

- Míriam Colón as Mercedes Cruz

- Clifton James as Hollis Pogue

- Jeff Monahan as young Hollis Pogue

- Ron Canada as Otis Payne

- Gabriel Casseus as young Otis Payne

- Joe Morton as Delmore Payne

- Carmen de Lavallade as Carolyn Payne

- Eddie Robinson as Chet Payne

- LaTanya Richardson Jackson as Sgt. Priscilla Worth

- Tony Plana as Ray

- Frances McDormand as Bunny

- Gonzales Castillo as Amado

- Richard Coca as Enrique

- Jesse Borrego as Danny Padilla

- Stephen Mendillo as Sgt. Cliff

- Oni Faida Lampley as Celie Payne

- Eleese Lester as Molly

- Tony Frank as Fenton

- Gordon Tootoosis as Wesley Birdsong

- Beatrice Winde as Minnie Bledsoe

- Chandra Wilson as Athena Johnson

- Richard Reyes as Jorge

Production[edit]

Filmmaker John Sayles decided to make a film about the Texas border after going there in 1978 to shoot a cameo for an earlier film he wrote, and then visiting the Alamo in San Antonio, and coming up with a script that "had elements of a Western, but it was more of a detective story. It was one of those rare instances where I wrote it and we got the money to make it right away."[4]

The movie was filmed in Del Rio, Eagle Pass and Laredo, Texas.[5]

Sayles did not want to film the flashback scenes with visible cuts to the present-day scenes, and instead utilized pans so the transitions occurred within a single camera shot.[6][7][4] These allowed the transitions to "feel like it was just a flow like time or like [a] river".[8] An example is the scene where a present-day Sam is seen in the same place in present day where he and Pilar have just strolled together discussing their past, and where Sam lingers to recollect a scene that took place on the same spot 23 years before between his 15-year old self and a 14-year old Pilar.[8]

Sayles cast newcomer Matthew McConaughey, whose only previous film was Richard Linklater's Dazed and Confused, in a major role because "I needed a guy who didn't have any star weight but who had the presence to play off against Kristofferson."[4]

Mason Daring's soundtrack uses music from a variety of genres, including juke joint music, conjunto, and country music, to highlight the melting pot of cultures in Rio County.[9]

Themes[edit]

The film deconstructs the concept of borders, both in the literal and figurative sense.[10][6] The film takes place in a border town (its name Frontera is the Spanish word for "border"),[11] along the U.S.-Mexico border. In Frontera, figurative barriers exist between different racial and cultural groups, specifically the Anglo, Black, and Tejano communities. The film goes on to subvert the idea of borders, as it depicts literal border crossings (such as Mercedes and Eladio immigrating to Texas from Mexico), as well as border crossings in a racial, generational, and cultural sense.[11][6]

Through its cross-cultural and time-spanning narrative, the film explores how people from disparate ethnicities and cultures are intertwined, past and present. Nuances and differences within and among specific communities are shown. For instance, Otis is African-American but is also of Indigenous descent.[11] Pilar believes she is fully Tejano, only to discover she is half-white. The Tejano community itself is comprised of Mexican, Chicano, Mexican American, Spanish, Hispano, American and/or Indigenous ancestry.[12] Mercedes is herself an immigrant from Mexico, but over the years has chosen to distance herself from that heritage, choosing to identify as "Spanish" and looking down on other Mexican immigrants.[11][13]

The moral border between "good people" and "bad people" is likewise complicated, as Sam learns the truth about his father and some of his unsavory dealings. Sam is intent on unraveling the inflated myths that surround Buddy as an upstanding sheriff.[14] He ultimately discovers that the father he despises is neither as bad as he has always believed him to be, nor as good as his burdensome legend depicts.[14] Intergenerational borders that divide Sam and Buddy, as well as Otis and Delmore Payne and Mercedes and Pilar Cruz, are eventually bridged as characters learn various truths about their parents and repair the fissures in strained relationships.[15]

Other themes include historical revisionism, mythmaking, and how legends are used to obscure inconvenient truths. The question of who gets to interpret history and why is most evident in the competing stories about Buddy, as well as in the classroom scene in which parents and teachers argue over the appropriate version of Texas history to teach high school students. In historical accounts of the Battle of the Alamo, it is often the heroic feats of Anglo figures like Davy Crockett and Jim Bowie that are celebrated, while the contributions of Mexicans, African-Americans, and Native Americans are relegated to the margins.[11] Sayles stated he wanted the film to address the concept of historical revisionism, saying "One of the things that 'Lone Star' is about, to me, is the way in which American culture has always, always been many cultures. [But] in many places, the dominant culture gets to write the history."[16][14]

The dismantling of myth is encapsulated with the film's final lines, "Forget the Alamo." "Remember the Alamo" is a famous battle cry that honors Texans' victory against the Mexicans at the Battle of the Alamo. The "Forget" line deconstructs the mythmaking behind the Alamo story and the barriers that separate Pilar and Sam—the racial barrier, as well as the barrier of their blood relation.[11] In an essay for The Criterion Channel, Domino Renee Perez writes, "The Alamo, both as a historical site and as a symbol, looms large in Texas mythmaking. But Sayles's film is more about revealing the dark secrets behind, rather than building up, a myth—the myth of Buddy Deeds. Pilar and Sam's resolve to forget represents a turn away from that legacy as they attempt to write their own futures, ones not beholden to any history."[11]

Writers noted that the opening classroom scene of parents challenging teachers takes on a prescient meaning in regards to the contemporary political climate and controversy over critical race theory.[11][7] In 2021, Texas passed a law that limits the manner and extent to which students learn about issues of race and racism in relation to American culture and history.[17]

Reception[edit]

Box office[edit]

Lone Star premiered at South by Southwest on March 14, 1996. It later screened in the Directors' Fortnight section at the Cannes Film Festival on May 10, 1996.[18] It was released in North American theaters on June 21, 1996 and ultimately made $13 million at the box office[2] on an estimated budget of $3-4.5 million.[14]

Critical response[edit]

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 91% of 140 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 8.6/10. The website's consensus reads: "Smart and absorbing, Lone Star represents a career high point for writer-director John Sayles – and '90s independent cinema in general."[19] On Metacritic, it has a score of 78 out of 100 based on reviews from 22 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[20]

Writing at the time of release, Janet Maslin of The New York Times said, "This long, spare, contemplatively paced film, scored with a wide range of musical styles and given a sun-baked clarity by Stuart Dryburgh's cinematography, is loaded with brief, meaningful encounters... And it features a great deal of fine, thoughtful acting, which can always be counted on in a film by Mr. Sayles".[21] "All the film's characters are flesh and blood", Maslin added, pointing particularly to the portrayals by Kristofferson, Canada, James, Morton and Colón.[21]

The Los Angeles Times's Kenneth Turan praised the film, writing its triumph is "how well it integrates Sayles' [social] concerns with the heightened tension and narrative drive the thriller form provides".[22] Film critics Dennis West and Joan M. West of Cineaste praised the psychological aspects of the film, writing, "Lone Star strikingly depicts the personal psychological boundaries that confront many citizens of Frontera as a result of living in such close proximity to the border".[23]

Roger Ebert awarded the film 4 out of 4 stars. His review read, "'Lone Star' is a great American movie, one of the few to seriously try to regard with open eyes the way we live now. Set in a town that until very recently was rigidly segregated, it shows how Chicanos, blacks, whites and Indians shared a common history, and how they knew one another and dealt with one another in ways that were off the official map. This film is a wonder -- the best work yet by one of our most original and independent filmmakers -- and after it is over, and you begin to think about it, its meanings begin to flower."[24]

Ann Hornaday, then writing for the Austin American-Statesman, declared it "a work of awesome sweep and acute perception", judging it "the most accomplished film of [Sayles'] 17-year career".[25] The Washington Post writer Hal Hinson characterized it as "a carefully crafted, unapologetically literary accomplishment."[26]

In 2004, William Arnold of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer said that the film was "widely regarded as Sayles' masterpiece", declaring that it had "captured the zeitgeist of the '90s as successfully as "Chinatown" did the '70s".[27]

In 2020, Hornaday compiled a list for The Washington Post titled "The 34 Best Political Movies Ever Made", in which she ranked Lone Star at number 10.[28] Describing Lone Star as Sayles' masterwork, she wrote, "A simultaneously epic and finely drawn intergenerational and time-shifting murder mystery set on the Texas-Mexico border, 'Lone Star' interrogates history, narrative and tidal shifts in power through the lens of race and immigration, but never at the expense of their complexities. Timely when it first came out, today it feels more relevant than ever."[28]

Accolades[edit]

The film received an Academy Award nomination for Best Screenplay for John Sayles.[29] The film also won the Belgian Grand Prix,[30] and the awards for Best Director and Best Screenplay from the Society of Texas Film Critics Awards. The screenplay was nominated for a Writers Guild of America Award, a BAFTA Award,[31] and a Golden Globe Award.[32]

Elizabeth Peña won the Independent Spirit Award for Best Supporting Female[33] and the BRAVO Award for Outstanding Actress in a Feature Film.[34] The film was nominated for three Independent Spirit Awards: Best Male Lead (Chris Cooper), Best Film, and Best Screenplay.[33]

The film is recognized by the American Film Institute in AFI's 10 Top 10 list in 2008 as a nominated Western Film.[35]

Home media[edit]

In 2023, The Criterion Collection announced they were releasing a 4K digital restoration of Lone Star, supervised by Sayles and cinematographer Stuart Dryburgh.[36] The restoration was released on Blu-ray disc on January 16, 2024. The edition includes a new interview with Dryburgh and a conversation between Sayles and filmmaker Gregory Nava.[15]

References[edit]

- ^ Molyneaux, Gerry (May 19, 2000). John Sayles: An Unauthorized Biography of the Pioneer Indy Filmmaker. St. Martin's Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-58063-125-9.

- ^ a b c "Lone Star (1996)". The Numbers. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ "Interviews with Cast and Director of Lone Star (1996)". Texas Archive of the Moving Image. Retrieved November 17, 2019.

- ^ a b c Hoad, Phil (February 26, 2024). "'I recently went back to the Texas border – and urinated on the wall': how we made Lone Star". The Guardian. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- ^ "The Border Towns of 'Lone Star'". Texas Film Commission. State of Texas, Office of the Governor. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ^ a b c Seitz, Matt Zoller (January 18, 2024). "Director John Sayles on the Making of 'Lone Star'". Texas Highways. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ a b Shaffer, Marshall (January 22, 2024). "Interview: John Sayles on Capturing Past and Present in Lone Star". Slant Magazine. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ a b Chaw, Walter (January 15, 2024). "We're So Short on Time: John Sayles on Lone Star". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ McDonald, Steven. "Lone Star Original Soundtrack". AllMusic. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ Cone, Nathan (February 27, 2024). "Borders dissolve in the Texas classic, 'Lone Star". Texas Public Radio. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Perez, Domino Renee (January 16, 2024). "Lone Star: Past Is Present". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ "Understanding and Celebrating Tejano History". College of Arts & Sciences. Texas A&M University. September 15, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ "The Women of Lone Star". US Ethnic Representations in Film. November 23, 2019. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Ratner, Megan (1996). "Borderlines". Filmmaker Magazine. The Gotham. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ^ a b "Lone Star". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ^ Adamek, Pauline (June 1996). "John Sayles interviewed for "Lone Star"". ArtsBeatLA. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ Lopez, Brian (December 2, 2021). "Republican bill that limits how race, slavery and history are taught in Texas schools becomes law". Texas Tribune. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (May 13, 1996). "Master of the Possible: Director John Sayles Exhibits a Determined Vision". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ "Lone Star". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 17, 2024.

- ^ "Lone Star". Metacritic. Retrieved July 17, 2024.

- ^ a b Maslin, Janet (June 21, 1996). "FILM REVIEW;Sleepy Texas Town With an Epic Story". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 3, 2010. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (June 21, 1996). "Human Relations the Star of Sayles' 'Lone' Mystery". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 20, 2021.

- ^ West, Dennis; West, Joan M. (Summer 1996). "Lone Star by R. Paul Miller, Maggie Renzi, John Sayles". Cineaste. Vol. 22, no. 3. pp. 34–36. JSTOR 41688927.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (July 3, 1996). "Lone Star". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved July 17, 2024 – via RogerEbert.com.

- ^ Hornaday, Ann (June 28, 1996). "'Lone Star' shines brightly". Austin American-Statesman. p. E1.

- ^ Hinson, Hal (July 12, 1996). "'Lone Star': Stagnant Sayles". The Washington Post. p. F6. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ Arnold, William (September 16, 2004). "John Sayles' timely political lampoon aims squarely at George W. Bush". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ a b Hornaday, Ann (January 23, 2020). "The 34 best political movies ever made". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ "The 69th Academy Awards | 1997". www.oscars.org. October 5, 2014. Retrieved July 17, 2024.

- ^ "Cinéma - Lundi 12 janvier 1998". Le Soir (in French). Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved July 17, 2024.

- ^ "Film in 1997 | BAFTA Awards". awards.bafta.org. Retrieved July 17, 2024.

- ^ "Lone Star". Golden Globes. Retrieved July 17, 2024.

- ^ a b "1997 Nominees and Winners" (PDF). Film Independent. p. 44. Retrieved July 17, 2024.

- ^ "1996 NCLR Bravo Award Winners". ALMA Awards. Archived from the original on September 11, 2002. Retrieved July 17, 2024.

- ^ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Criterion Announces January Releases". blu-ray.com. October 16, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

External links[edit]

- Lone Star at IMDb

- Lone Star at AllMovie

- Lone Star at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Lone Star at the TCM Movie Database

- Lone Star at Box Office Mojo

- Lone Star essay at Bad Subjects magazine by Tomás Sandoval, discusses the historical aspects of film (archived)

- Lone Star film review on YouTube by Siskel & Ebert

- Lone Star film trailer on YouTube

- 1996 films

- 1996 independent films

- 1990s mystery films

- 1996 romantic drama films

- 1996 Western (genre) films

- American independent films

- American mystery films

- American romantic drama films

- American Western (genre) films

- Castle Rock Entertainment films

- Films directed by John Sayles

- Films set in Texas

- Films shot in Texas

- Murder mystery films

- Films about immigration to the United States

- Films about sibling incest

- Contemporary Western films

- Films with screenplays by John Sayles

- Columbia Pictures films

- Sony Pictures Classics films

- Films set in 1957

- Films set in 1996

- Films about Mexican Americans

- Films scored by Mason Daring

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s American films