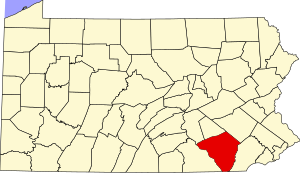

Lancaster County, Pennsylvania

Lancaster County | |

|---|---|

| |

Location within the U.S. state of Pennsylvania | |

Pennsylvania's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 40°02′N 76°15′W / 40.04°N 76.25°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | May 10, 1729 |

| Named for | Lancaster, Lancashire |

| Seat | Lancaster |

| Largest city | Lancaster |

| Area | |

• Total | 984 sq mi (2,550 km2) |

| • Land | 944 sq mi (2,440 km2) |

| • Water | 40 sq mi (100 km2) 4.1% |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 552,984 |

• Estimate (2022)[1] | 556,629 |

| • Density | 560/sq mi (220/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 11th |

| Website | www |

Lancaster County (/ˈlæŋkɪstər/; Pennsylvania Dutch: Lengeschder Kaundi), sometimes nicknamed the Garden Spot of America or Pennsylvania Dutch Country, is a county in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 552,984, making it Pennsylvania's sixth-most populous county.[2] Its county seat is also Lancaster.[3] Lancaster County comprises the Lancaster metropolitan statistical area. The county is part of the South Central region of the state.[a]

Lancaster County is a tourist destination with its Amish community being a major attraction. The ancestors of the Amish began to immigrate to colonial Pennsylvania in the early 18th century to take advantage of the religious freedom offered by William Penn,[4] as well as the area's rich soil and mild climate.[5] They were joined by French Huguenots fleeing the religious persecution of Louis XIV.[6][7] There were also significant numbers of English, Welsh and Ulster Scots (also known as the Scotch-Irish in the colonies).

History

[edit]The area that became Lancaster County was part of William Penn's 1681 charter.[8] John Kennerly received the first recorded deed from Penn in 1691.[9] Although Matthias Kreider was said to have been in the area as early as 1691, there is no evidence that any Europeans settled in Lancaster County before 1710.[10]

Lancaster County was part of Chester County, Pennsylvania, until May 10, 1729, when it was organized as the colony's fourth county.[11] It was named after the city of Lancaster in the county of Lancashire in England, the native home of John Wright, an early settler.[12] As settlement increased, six other counties were subsequently formed from territory directly taken, in all or in part, from Lancaster County: Berks (1752), Cumberland (1750), Dauphin (1785), Lebanon (1813), Northumberland (1772), and York (1749).[11] Many other counties were in turn formed from these six.

Indigenous peoples

[edit]Indigenous peoples had occupied the areas along the waterways for thousands of years, and established varying cultures. Historic Native American tribes in the area at the time of European encounter included the Shawnee, Susquehannock, Gawanese, Lenape (or Delaware), and Nanticoke peoples, who were from different language families and had distinct cultures.[13]

Among the earliest recorded inhabitants of the Susquehanna River valley were the Iroquoian-speaking Susquehannock, whose name was derived from the Lenape term for "Oyster River People". (The Lenape spoke an Algonquian language.)[14] The English called them the Conestoga, after the name of their principal village, Gan'ochs'a'go'jat'ga ("Roof-place" or "town"), anglicized as "Conestoga."[15] Other places occupied by the Susquehannock were Ka'ot'sch'ie'ra ("Place-crawfish"), where present-day Chickisalunga developed, and Gasch'guch'sa ("Great-fall-in-river"), now called Conewago Falls, Lancaster County.[16]

Other Native tribes, as well as early European settlers, considered the Susquehannock a mighty nation, experts in war and trade. They were beaten only by the combined power of the Five Nation Iroquois Confederacy, after colonial Maryland withdrew its support. After 1675, the Susquehannock were totally absorbed by the Iroquois. A handful were settled at "New Conestoga," located along the south bank of the Conestoga River in Conestoga Township of the county. They helped staff an Iroquois consulate to the English in Maryland and Virginia (and later, Pennsylvania). By the 1720s, the colonists considered the Conestoga Indians as a "civilized" or "friendly tribe," having been converted in large part to Christianity, speaking English as a second language, making brooms and baskets for sale, and naming children after their favorite neighbors.[17]

The outbreak of Pontiac's War in the summer of 1763, coupled with the ineffective policies of the provincial government, aroused widespread settler suspicion and hatred against all Indians in the frontier counties, without distinguishing among hostile and friendly peoples. On December 14, 1763, the Paxton Boys, led by Matthew Smith and Capt. Lazarus Stewart, attacked Conestoga, killing the six Indians present, and burning all the houses. Officials sheltered the tribe's fourteen survivors in protective custody in the county jail, but the Paxton Boys returned on December 27, broke into the jail, and massacred the remaining natives. The lack of effective government control and widespread sympathy in the frontier counties for the murderers meant they were never discovered or brought to justice.[18]

Maryland-Pennsylvania boundary dispute

[edit]Pennsylvania had a longstanding dispute with Maryland about the southern border of the province and Lancaster County. Nine years of armed clashes accompanied the Maryland-Pennsylvania boundary dispute, which began soon after the 1730 establishment of Wright's Ferry across the Susquehanna River. Lord Baltimore believed that his grant[19] to Maryland extended to the 40th parallel.[20] This was about halfway between present-day Lancaster and the town of Willow Street, Pennsylvania. This line of demarcation would have resulted in Philadelphia being included in Maryland.

New settlers began to cross the Susquehanna. In 1730, the Wright's Ferry services were licensed and officially begun. Starting in mid-1730, Thomas Cresap, acting as an agent of Lord Baltimore, began confiscating the newly settled farms near present-day Peach Bottom and Columbia, Pennsylvania, which at the time this was not named but was later called Wright's Ferry. Believing he controlled this land under his grant, Lord Baltimore wanted the income from the lands. He believed he had a defensible claim established on the west bank of the Susquehanna River since 1721, and that his demesne and grant extended to forty degrees north. If he allowed Pennsylvanians to settle his lands without reacting, he believed, their squatting would constitute a counter claim.

Cresap established a second ferry in the upper Conejohela downriver from John Wright's, near Peach Bottom. He demanded that settlers either move out or pay Maryland for the right-bank lands. Settlers believed they already had rights to these under Pennsylvania grants. Cresap drove off settlers by vandalizing farms and killing livestock; he pushed out settlers from southern York and Lancaster counties. He gave the abandoned lands to his followers. If a follower was arrested by Lancaster authorities, the Marylanders would break him out of the lockup.

Lord Baltimore negotiated a compromise in 1733, but Cresap ignored it and continued his raids. A deputy was sent to arrest him in 1734, and Cresap killed him at the door. The Pennsylvania governor demanded that Maryland arrest Cresap for murder; the Maryland governor instead commissioned him as a captain in the militia. In 1736, Cresap was finally arrested; he was jailed until 1737 when the King intervened. In 1750, a court decided that, by failing to develop the land with settlers, Lord Baltimore had forfeited his rights to a twenty-mile (32 km) swath of land.[20] In 1767, a new Pennsylvania-Maryland border was officially established by the Mason-Dixon line.

Diversity of settlers

[edit]

The names of the original Lancaster County townships reflect the diverse national origins of settlers in the new county:[21] two had Welsh names (Caernarvon and Lampeter), three had Native American names (Cocalico, Conestoga and Peshtank or Paxton), six were English (Warwick, Lancaster, Martic, Sadsbury, Salisbury and Hempfield); four were Irish (Donegal, Drumore, Derry, and Leacock), reflecting mostly Scots-Irish (or Ulster Scots) from Ulster, a province in the north of Ireland; Manheim was German, Lebanon came from the Bible, a basis of all the European cultures; and Earl was a translation of the German surname of Graf or Groff.[22]

19th-century statesmen

[edit]Lancaster County's native son James Buchanan, a Democrat, was elected as the 15th President of the United States in 1856,[23] the first Pennsylvania native to hold the presidency. His home Wheatland is now operated as a house museum in Lancaster.[24]

Thaddeus Stevens, the noted Radical Republican, represented Lancaster County in the United States House of Representatives from 1849 to 1853 and from 1859 until his death in 1868.[25] Stevens left a $50,000 (~$1,000,000 in 2023) bequest to establish an orphanage.[26] This property eventually was developed as the state-owned Thaddeus Stevens College of Technology. Stevens and Buchanan were both buried in Lancaster.[27]

Slavery and the Christiana incident

[edit]Pennsylvania passed its gradual abolition law in 1780.[28] The law, which freed the children of duly registered enslaved women at the age of twenty-eight, was a compromise between anti-slavery conviction and respect for white property rights.[29] By the time the U.S. Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, Pennsylvania was effectively a free state, although it did not formally abolish slavery completely until the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment. It did, however, pass a personal liberty law in 1847 that made it difficult for southerners to recover any enslaved persons who made their way into Pennsylvania.[30]

Lying just north of the Mason-Dixon line and bordered by the Susquehanna River, which had been a traditional route from the Chesapeake Bay watershed into the heart of what became Pennsylvania, Lancaster County was a significant destination of the Underground Railroad in the antebellum years. Many residents of German descent opposed slavery and cooperated in aiding fugitive slaves. Local Lancaster County resident Charles Spotts found 17 stations.[31] They included hiding places with trap doors, hidden vaults, a cave, and one with a brick tunnel leading to Octoraro Creek, a tributary of the Susquehanna.[citation needed]

As a wealthy Maryland wheat farmer, Edward Gorsuch had manumitted several slaves in their 20s. He allowed his slaves to work for cash elsewhere during the slow season. Upon finding some of his wheat missing, he thought his slaves had sold it to a local farmer. His slaves Noah Buley, Nelson Ford, George Ford, and Joshua Hammond, fearing his bad temper, fled across the Mason–Dixon line to the farm of William Parker, a mulatto free man and abolitionist who lived in Christiana, Pennsylvania. Parker, 29, was a member of the Lancaster Black Self-Protection Society and known to use violence to defend himself and the fugitive slaves who sought refuge in the area.[citation needed]

Gorsuch obtained four warrants and organized four parties, which set out separately with federal marshals to recover his property—the four slaves. He was killed and others were wounded. While Gorsuch was legally entitled to recover his slaves under the Fugitive Slave Act, it is not clear who precipitated the violence. The incident was variously called the "Christiana Riot", "Christiana Resistance", the "Christiana Outrage", and the "Christiana Tragedy". The Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society helped provide defense for the suspects charged in the case.[citation needed]

The event frightened slaveholders, as black men not only fought back but prevailed. Some feared this would inspire enslaved blacks and encourage rebelliousness. The case was prosecuted in U.S. District Court in Philadelphia under the Fugitive Slave Act, which required citizens to cooperate in the capture and return of fugitive slaves. The disturbance increased regional and racial tensions. In the North, it added to the push to abolish slavery.[32]

In September 1851, the grand jury returned a "true bill" (indictment) against 38 suspects, who were held at Moyamensing Prison in Philadelphia, awaiting trial. U.S. District Judge Robert Cooper Grier ruled that the men could be tried for treason.[33]

The only person actually tried was Castner Hanway, a European-American man. On November 15, 1851, he was tried for liberating slaves taken into custody by U.S. Marshal Kline, as well as for resisting arrest, conspiracy, and treason. Hanway's responsibility for the violent events was unclear. He was reported as one of the first on the scene where Gorsuch and others of his party were attacked, and he and his horse provided cover for Dickerson Gorsuch and Dr. Pearce, who were wounded. The jury deliberated 15 minutes before returning a Not Guilty. Among the five defense lawyers, recruited by the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, was U.S. Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, who had practiced law in Lancaster County since at least 1838.[34]

Religious history

[edit]The oldest surviving dwelling of European settlers in the county[35] is that of Mennonite Bishop Hans Herr, built in 1719. In 1989, Donald Kraybill counted 37 distinct religious bodies/organizations, with 289 congregations and 41,600 baptized members, among the plain sects who are descendants of the Anabaptist Mennonite immigrants to Lancaster County.[36] The Mennonite Central Committee in Akron supports relief in disasters[37] and provides manpower and material to local organizations in relief efforts.[38]

The town of Lititz was originally planned as a closed community, founded early in the 1740s by members of the Moravian Church. The town eventually grew and welcomed its neighbors. The Moravian Church established Linden Hall School for Girls in 1746; it is one of the earliest educational institutions in continuous operation in the United States.[39]

In addition to the Ephrata Cloister, the United Brethren in Christ and the Evangelical United Brethren (EUB) trace their beginnings to a 1767 meeting[40] at the Isaac Long barn, near the hamlet of Oregon, in West Lampeter Township.[41] The EUB, a German Methodist church, merged in 1968 with the traditionally English Methodist Episcopal Church to become the United Methodist Church.[42]

The first Jewish resident was Isaac Miranda [citation needed], from the Sephardic Jewish community of London, who owned property before the town and county were organized in 1730. Ten years later several Jewish families had settled in the town; on February 3, 1747, a deed to Isaac Nunus Ricus (Henriques) and Joseph Simon was recorded, conveying 0.5 acres (0.20 ha) of land "in trust for the society of Jews settled in and about Lancaster," to be used as a place of burial. This cemetery is still used by Congregation Shaarai Shomayim;[43] it is considered the nation's fourth-oldest Jewish cemetery.

As of 2010, Lancaster County is home to three synagogues: the Orthodox Degel Israel; the Conservative Beth El; and the Reform Shaarai Shomayim. In 2003 Rabbi Elazar Green & Shira Green founded the Chabad Jewish Enrichment Center, a branch of the Chabad Lubavitch movement, that focuses on serving the Jewish students of Franklin and Marshall College, as well serving the general community with specific religious services. The Lancaster Mikvah Association runs a mikveh on Degel Israel's property. Central PA Kosher Stand is operated at Dutch Wonderland, a seasonal amusement park.

This area was also settled by French Huguenots, who had fled to England and then the colonies in the late 1600s and early 1700s to escape Catholic persecution in France. Isaac LeFèvre and a group of other Huguenots settled in the Pequea Creek area.

Inventions

[edit]

- Fraktur, the artistic and elaborate 18th- century and 19th-century hand-illuminated folk art inspired by German blackface type, originated at Johann Conrad Beissel's cloister of German Seventh Day Baptists in Ephrata.[44]

- The first battery-powered watch, the Hamilton Electric 500, was released in 1957 by the Hamilton Watch Company.[45]

- The Pennsylvania Long Rifle,[46] otherwise known as the "Kentucky" (Long) Rifle.

- The Conestoga wagon,[47] which started the US practice of opposing vehicles passing each other to the right.

- The Stogie cigar[48] "Stogie" is shortened from "Conestoga".

- The Amish quilt, a highly utilitarian art form, dates from 1849 in Lancaster County.[49]

Geography

[edit]According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 984 square miles (2,550 km2), of which 944 square miles (2,440 km2) is land and 40 square miles (100 km2) (4.1%) is water.[50]

Climate

[edit]Most of the county has a hot-summer humid continental climate (Dfa) and the hardiness zones are 6b and 7a. The most recent temperature averages show areas along the Susquehanna River and in the lower Conestoga Valley to have a humid subtropical climate (Cfa.)

| Climate data for Lancaster, Pennsylvania (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1949–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 70 (21) |

82 (28) |

88 (31) |

93 (34) |

99 (37) |

97 (36) |

103 (39) |

101 (38) |

99 (37) |

93 (34) |

86 (30) |

76 (24) |

103 (39) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 39.9 (4.4) |

42.8 (6.0) |

52.0 (11.1) |

64.6 (18.1) |

74.5 (23.6) |

82.7 (28.2) |

87.0 (30.6) |

85.1 (29.5) |

78.2 (25.7) |

66.4 (19.1) |

54.8 (12.7) |

44.4 (6.9) |

64.4 (18.0) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 31.0 (−0.6) |

33.2 (0.7) |

41.4 (5.2) |

52.6 (11.4) |

62.4 (16.9) |

71.2 (21.8) |

75.9 (24.4) |

74.1 (23.4) |

66.9 (19.4) |

55.1 (12.8) |

44.4 (6.9) |

35.7 (2.1) |

53.7 (12.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 22.2 (−5.4) |

23.6 (−4.7) |

30.9 (−0.6) |

40.5 (4.7) |

50.4 (10.2) |

59.7 (15.4) |

64.7 (18.2) |

63.0 (17.2) |

55.6 (13.1) |

43.7 (6.5) |

34.0 (1.1) |

27.1 (−2.7) |

42.9 (6.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −16 (−27) |

−9 (−23) |

−2 (−19) |

16 (−9) |

21 (−6) |

33 (1) |

46 (8) |

37 (3) |

34 (1) |

23 (−5) |

11 (−12) |

−3 (−19) |

−16 (−27) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.01 (76) |

2.52 (64) |

3.50 (89) |

3.54 (90) |

3.65 (93) |

4.09 (104) |

4.51 (115) |

3.60 (91) |

4.82 (122) |

4.18 (106) |

3.26 (83) |

3.47 (88) |

44.15 (1,121) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 6.1 (15) |

7.4 (19) |

3.4 (8.6) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.6 (1.5) |

3.4 (8.6) |

21.4 (54) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.0 | 8.8 | 10.5 | 10.9 | 12.7 | 11.1 | 10.3 | 9.7 | 9.5 | 9.9 | 9.6 | 10.9 | 123.9 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 2.7 | 2.7 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 8.1 |

| Source: NOAA[51][52] | |||||||||||||

Watersheds

[edit]Almost all of Lancaster County is in the Chesapeake Bay drainage basin, via the Susquehanna River watershed (the exception is a small unnamed tributary of the West Branch of Brandywine Creek that rises in eastern Salisbury Township and is part of the Delaware River watershed).[53] The major streams in the county (with percent area drained) are: Conestoga River and Little Conestoga Creek (31.42%); Pequea Creek (15.02%); Chiques Creek (or Chickies Creek, 12.07%); Cocalico Creek (11.25%); Octoraro Creek (10.74%); and Conowingo Creek (3.73%).[54]

Protected areas

[edit]Lancaster County is home to Susquehannock State Park, located on 224 acres (91 ha) overlooking the Susquehanna River in Drumore Township.[55] One of the three tracts comprising William Penn State Forest, the 10-acre (4.0 ha) Cornwall fire tower site, is located in northern Penn Township near the Lebanon County border. The site, with its 1923 fire tower, was acquired by the state in January 1935.[56]

There are six Pennsylvania State Game Lands for hunting, trapping, and fishing located in Lancaster County. They are numbers (with location and area): 46 (near Hopeland, 5,035 acres (2,038 ha)), 52 (near Morgantown, 1,447 acres (586 ha)), 136 (near Kirkwood, 91 acres (37 ha)), 156 (near Poplar Grove, 4,537 acres (1,836 ha)), 220 (near Reinholds, 96 acres (39 ha)), and 288 (near Martic Forge, 89 acres (36 ha)).[57]

The county's southern portion has some protected serpentine barrens, a rare ecosystem where toxic metals in the soil inhibit plant growth, resulting in the formation of natural grassland and savanna. These barrens include the New Texas Serpentine Barrens, privately owned land managed by The Nature Conservancy,[58] and Rock Springs Nature Preserve, a publicly accessible preserve with hiking trails owned and managed by the Lancaster County Conservancy.[59]

Lancaster County leads the nation in farmland preservation. Organizations such as the Lancaster Farmland Trust, the Lancaster County Agricultural Preservation Board, and multiple municipalities work in partnership with landowners to preserve their farms and way of life for future generations by placing a conservation easement on their property. A conservation easement restricts real estate development, commercial and industrial uses, and certain other activities on the land that are mutually agreed upon by the grantees and the property owner. After ceding their development rights, landowners continue to manage and own their properties and may receive significant tax breaks. The conservation easement ensures that the land will remain available for agricultural use forever. Lancaster Farmland Trust is a private, non-profit organization that works closely with the vast Amish and Plain-Sect communities of Lancaster County to ensure their farms will retain their agricultural value. Together with the Lancaster County Agricultural Preserve Board, the county has preserved more than 100,000 acres (40,000 ha) of preserved farmland in the county—a first in the nation.[60]

Seismicity

[edit]Lancaster County lies on the general track of the Appalachian Mountains. As a result, residual seismic activity from ancient faulting occasionally produces minor earthquakes of magnitude 3 to 4. On December 27, 2008, a 3.3 magnitude earthquake was widely felt in the Susquehanna Valley but caused no damage to structures.[61]

Adjacent counties

[edit]- Lebanon County (North)

- Berks County (Northeast)

- Dauphin County (Northwest)

- Cecil County, Maryland (South)

- Harford County, Maryland (Southwest)

- Chester County (East)

- York County (West)

Flora and fauna

[edit]The bog turtle was first discovered and identified in Lancaster County by botanist Gotthilf Heinrich Ernst Muhlenberg, who discovered the turtle species while surveying the area's flora. The species was named Muhlenberg's tortoise in 1801, but renamed bog turtle, its present common name, in 1956.[62]

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 36,081 | — | |

| 1800 | 43,403 | 20.3% | |

| 1810 | 53,927 | 24.2% | |

| 1820 | 68,336 | 26.7% | |

| 1830 | 76,631 | 12.1% | |

| 1840 | 84,203 | 9.9% | |

| 1850 | 98,944 | 17.5% | |

| 1860 | 116,314 | 17.6% | |

| 1870 | 121,340 | 4.3% | |

| 1880 | 139,447 | 14.9% | |

| 1890 | 149,095 | 6.9% | |

| 1900 | 159,241 | 6.8% | |

| 1910 | 167,029 | 4.9% | |

| 1920 | 173,797 | 4.1% | |

| 1930 | 196,882 | 13.3% | |

| 1940 | 212,504 | 7.9% | |

| 1950 | 234,717 | 10.5% | |

| 1960 | 278,359 | 18.6% | |

| 1970 | 319,693 | 14.8% | |

| 1980 | 362,346 | 13.3% | |

| 1990 | 422,822 | 16.7% | |

| 2000 | 470,658 | 11.3% | |

| 2010 | 519,445 | 10.4% | |

| 2020 | 552,984 | 6.5% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 558,589 | 1.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[63] 1790–1960[64] 1900–1990[65] 1990–2000[66] 2010–2019[67] 2020[2] | |||

| Lancaster County Demographics[68] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | County | State | U.S. |

| White | 91.0% | 83.2% | 77.7% |

| African American | 4.7% | 11.5% | 13.2% |

| Native American | 0.4% | 0.3% | 1.2% |

| Asian | 2.1% | 3.1% | 5.3% |

| Pacific Islander | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.2% |

| Two or more races | 1.8% | 1.8% | 2.4% |

| Hispanic/Latino of any race | 9.5% | 6.3% | 17.1% |

| White alone, not Hispanic or Latino | 83.6% | 78.4% | 62.6% |

As of the 2010 census,[69] there were 519,445 people. The population density was 561 people per square mile (217 people/km2). There were 193,602 households. Of that number 135,401 (69.9%) were families. Of those families, 120,112 (88.7%) had children under the age of 18. There were 202,952 housing units at an average density of 215 per square mile (83/km2). The average household size was 2.62 and the average family size was 3.13.

In the county, the population was spread out, with 24.8% under the age of 18 and 15.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38.2 years. For every 100 females, there were 95.10 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 91.60 males.

5.58% of the population and 8.37% of the children aged 5–17 reported speaking Pennsylvania Dutch, German, or Dutch at home, while a further 4.97% of the population spoke Spanish.[70] 39.8% were of German, 11.8% United States or American, 7.2% Irish and 5.7% English ancestry.

2020 census

[edit]| Race | Num. | Perc. |

|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 440,613 | 79.68% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 19,536 | 3.53% |

| Native American (NH) | 522 | 0.01% |

| Asian (NH) | 13,939 | 2.52% |

| Pacific Islander (NH) | 110 | 0.02% |

| Other/Mixed (NH) | 17,093 | 3.1% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 61,171 | 11.1% |

Plain Anabaptist (Amish) groups

[edit]Lancaster County Anabaptist community founded in c. 1760, has the world's largest Amish settlement, with 37,000 people in 220 church districts in 2017, or about 7% of the county's population.[72] By 2021 the Amish population increased to almost 42,000.[73][74] The Lancaster Amish affiliation is relatively liberal concerning the use of technologies compared to other Amish affiliations.

Historically speaking, the Amish population in 1970 numbered only about 7,000; that climbed to about 12,400 by 1990 and 16,900 by 2000.[75] It has doubled since then.

Lancaster also hosts other Plain Anabaptist groups. As of 2000, there are about 3,000 Old Order Mennonites of the Groffdale Conference who drive black top buggies instead of the grey top buggies of the Amish in Lancaster County. Other buggy-using Old Order Mennonites in Lancaster County are subgroups of the Stauffer Mennonites with 283 baptized members and the Reidenbach Mennonites with 232. There are about 4,000 members of the car-driving Weaverland Old Order Mennonite Conference. A congregation of 83 members of the Old Order River Brethren lives there as well as 84 members of the Reformed Mennonite Church who have retained the most conservative form of Plain dress of all Plain groups. There are 74 members of the Old German Baptist Brethren in Lancaster County.[76]

-

An Amish family in a traditional Amish buggy in the county

-

Amish children in the back of a buggy on the road

-

Amish farmers use only horse power to cultivate their land

-

Amish crops in the county

-

An Amish dairy farm

-

Persons speaking an Indo-European language at home other than English or Spanish (among adults 18+), a vast majority of them speak Pennsylvania German. (ACS 2019 5-year estimate).

Religion

[edit]- Protestant: 38% (of whom Evangelical Protestant 23.7%, Mainline Protestant 13.8%, Black Protestant 0.4%)

- Roman Catholic: 9.9%

- Eastern Orthodox Christian: 0.3%

- Other: 1.1%

- Unaffiliated: 50.9%

Dialect

[edit]Some County residents speak with a Pennsylvania Dutch-influenced dialect.[77] This is most common in the Lancaster, Lebanon, York, and Harrisburg areas, and incorporates influences from the Pennsylvania Dutch in dialect and in nomenclature.

Metropolitan statistical area

[edit]The U.S. Office of Management and Budget has designated Lancaster County as the Lancaster, PA Metropolitan Statistical Area.[78] With a population of 552,984 as of the 2020 U.S. census, the Lancaster, PA metropolitan area is the sixth most populous metropolitan area in Pennsylvania, after the Delaware Valley, Greater Pittsburgh, the Lehigh Valley, the Harrisburg–Carlisle metropolitan statistical area, and the Wyoming Valley.

On a national level, the Lancaster, PA metropolitan area is the 104th most populous metropolitan statistical area as of the 2020 census and the 102nd most populous primary statistical area in the United States as of the 2010 census.[79][80]

Government and politics

[edit]Political party affiliation

[edit]| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party(ies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2024 | 166,261 | 57.20% | 120,120 | 41.32% | 4,292 | 1.48% |

| 2020 | 160,209 | 56.94% | 115,847 | 41.17% | 5,319 | 1.89% |

| 2016 | 137,914 | 56.33% | 91,093 | 37.21% | 15,825 | 6.46% |

| 2012 | 130,669 | 58.50% | 88,481 | 39.62% | 4,201 | 1.88% |

| 2008 | 126,568 | 55.21% | 99,586 | 43.44% | 3,095 | 1.35% |

| 2004 | 145,591 | 65.77% | 74,328 | 33.58% | 1,453 | 0.66% |

| 2000 | 115,900 | 66.09% | 54,968 | 31.34% | 4,499 | 2.57% |

| 1996 | 92,875 | 59.81% | 49,120 | 31.63% | 13,291 | 8.56% |

| 1992 | 88,447 | 55.22% | 44,255 | 27.63% | 27,478 | 17.15% |

| 1988 | 96,979 | 70.77% | 38,982 | 28.45% | 1,068 | 0.78% |

| 1984 | 99,090 | 75.63% | 31,308 | 23.90% | 618 | 0.47% |

| 1980 | 79,963 | 67.25% | 30,026 | 25.25% | 8,908 | 7.49% |

| 1976 | 72,106 | 65.74% | 35,533 | 32.40% | 2,037 | 1.86% |

| 1972 | 81,036 | 75.64% | 24,223 | 22.61% | 1,879 | 1.75% |

| 1968 | 69,953 | 64.59% | 29,870 | 27.58% | 8,484 | 7.83% |

| 1964 | 52,243 | 49.52% | 53,041 | 50.27% | 224 | 0.21% |

| 1960 | 78,390 | 70.06% | 33,233 | 29.70% | 266 | 0.24% |

| 1956 | 69,026 | 72.05% | 26,538 | 27.70% | 237 | 0.25% |

| 1952 | 64,193 | 69.23% | 28,146 | 30.36% | 382 | 0.41% |

| 1948 | 46,306 | 67.60% | 21,308 | 31.11% | 885 | 1.29% |

| 1944 | 44,888 | 61.77% | 27,353 | 37.64% | 432 | 0.59% |

| 1940 | 44,939 | 58.05% | 32,210 | 41.61% | 269 | 0.35% |

| 1936 | 42,272 | 51.38% | 38,454 | 46.74% | 1,547 | 1.88% |

| 1932 | 34,502 | 56.54% | 24,406 | 40.00% | 2,111 | 3.46% |

| 1928 | 55,530 | 81.43% | 12,146 | 17.81% | 516 | 0.76% |

| 1924 | 42,787 | 73.73% | 12,091 | 20.83% | 3,156 | 5.44% |

| 1920 | 29,549 | 72.88% | 9,521 | 23.48% | 1,472 | 3.63% |

| 1916 | 20,292 | 63.42% | 10,016 | 31.30% | 1,688 | 5.28% |

| 1912 | 12,668 | 36.95% | 8,574 | 25.01% | 13,040 | 38.04% |

| 1908 | 23,523 | 71.43% | 8,109 | 24.62% | 1,299 | 3.94% |

| 1904 | 26,083 | 76.54% | 7,092 | 20.81% | 902 | 2.65% |

| 1900 | 23,230 | 71.77% | 8,437 | 26.07% | 701 | 2.17% |

| 1896 | 24,337 | 72.67% | 8,145 | 24.32% | 1,008 | 3.01% |

| 1892 | 20,126 | 64.46% | 10,326 | 33.07% | 770 | 2.47% |

| 1888 | 21,976 | 66.56% | 10,495 | 31.79% | 545 | 1.65% |

| 1884 | 19,848 | 65.85% | 9,953 | 33.02% | 340 | 1.13% |

| 1880 | 19,489 | 64.11% | 10,789 | 35.49% | 120 | 0.39% |

Lancaster County was the home of the final pre-American Civil War U.S. President, James Buchanan, a Democrat. Since the Civil War, however, Lancaster County has been a Republican stronghold. The GOP controls the vast majority of county and municipal elected offices in Lancaster County.[83] Specifically, the row offices and all but one county commission seat are held by Republicans, and the GOP holds all but two state legislative seats covering the county. Republicans also hold a majority of registered voters in the county.

In September 2008, the Democratic Party reached the benchmark of 100,000 registered voters for the first time in the county's history.[83][84] The party had just 82,171 registered Democrats in 2004.[83] As of 2008[update], the ratio of Republicans to Democrats in Lancaster County now stands at 1.8 Republicans to 1 Democrat, down from a 3–1 advantage for the Republicans in the late 1990s.[83] Even with these gains, the county is still powerfully Republican downballot; the only real pockets of Democratic influence are in the city of Lancaster. Reflecting this, the only elected Democrats representing a significant portion of the county at the state or federal level hold state house seats anchored in Lancaster city and its closest-in suburbs.

Lancaster County has only ever voted for a Democratic presidential nominee once since James Buchanan in 1856, a resident of the city of Lancaster.[85] In 1964, Lyndon Johnson carried Lancaster County as part of his 44-state landslide, winning by 798 votes, less than a single percentage point. Franklin D. Roosevelt failed to carry the county during any of his four successful runs for president, coming within 4,000 votes of carrying it in his 46-state landslide of 1936. In 2008, Barack Obama became the first Democrat to garner 40 percent of the county's vote since Johnson, and the second since Franklin D. Roosevelt. Donald Trump earned 56 percent of the vote in both campaigns, with Joe Biden becoming the third Democrat in 80 years to win 40 percent of the county's vote.

According to the Secretary of State's office, Republicans hold a majority of the voters in Lancaster County.

| Lancaster County Voter Registration Statistics as of October 28, 2024[86] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Political Party | Total Voters | Percentage | |||

| Republican | 187,128 | 51.13% | |||

| Democratic | 114,789 | 31.36% | |||

| No party affiliation | 46,815 | 12.79% | |||

| Minor parties | 17,276 | 4.72% | |||

| Total | 366,008 | 100.00% | |||

Elected officials

[edit]United States Senate

[edit]| Senator | Party |

|---|---|

| [[Beans] | Democratic |

| John Fetterman | Democratic |

United States House of Representatives

[edit]| District | Representative | Party |

|---|---|---|

| 11 | Lloyd Smucker | Republican |

| District | Representative | Party |

|---|---|---|

| 13 | Scott Martin | Republican |

| 36 | Ryan Aument | Republican |

| District | Representative | Party |

|---|---|---|

| 37 | Mindy Fee | Republican |

| 41 | Brett Miller | Republican |

| 43 | Keith Greiner | Republican |

| 49 | Ismail Smith-Wade-El | Democratic |

| 96 | Mike Sturla | Democratic |

| 97 | Steven Mentzer | Republican |

| 98 | Tom Jones | Republican |

| 99 | David Zimmerman | Republican |

| 100 | Bryan Cutler | Republican |

Commissioners

[edit]| Office | Holder | Party |

|---|---|---|

| Chairman | Joshua Parsons | Republican |

| Vice-chairman | Ray D'Agostino | Republican |

| County Commissioner | John Trescot | Democratic |

Source:[89]

Row officers

[edit]| Office | Holder | Party |

|---|---|---|

| Clerk of Courts | Mary Anater | Republican |

| Controller | Lisa Colon | Republican |

| Coroner | Dr. Stephen Diamantoni, M.D. | Republican |

| District Attorney | Heather Adams, Esq. | Republican |

| Prothonotary | Andrew Spade | Republican |

| Recorder of Deeds | Ann Hess | Republican |

| Register of Wills | Ann Cooper | Republican |

| Sheriff | Chris Leppler[90] | Republican |

| Treasurer | Amber Green | Republican |

Sources:,[91][92][93][94][95][96][97][98][99]

Economy

[edit]

In 2021, the county had a per capita personal income (PCPI) of $61,547, 96% of the national average. This reflects a growth of 5.7% from the prior year, versus a 7.3% growth for the nation as a whole.[100] The county poverty rate was 8.8% compared to a national rate of 11.6%.[68]

In 2005, Lancaster County was 10th of all counties in Pennsylvania with 17.7% of its workforce employed in manufacturing; the state averages 13.7%, and the leader, Crawford County, has only 25.1%.[101]

Lancaster County lags in information workers. It ranks 31st in the state with 1.3% of the workforce; the state as a whole employs 2.1% in information technology.[102]

The county ranks 11th in the state in managerial and financial workers, despite having 12.5% of the workforce in those occupations (versus the state average of 12.8%). The state leaders are Chester County with 20.5% and Montgomery County with 18.5%.[103]

With 17.3% working in the professions, Lancaster County is 31st in Pennsylvania, compared to a state average of 21.5%. Centre County leads with 31.8%, undoubtedly due to Penn State's giant footprint in an otherwise rural county, but the upscale Philadelphia suburbs of Montgomery County give them 27.2%.[104]

Lancaster County ranks even lower, 34th, in service workers, with 13.3% of the workforce, compared to a state average of 15.8%. Philadelphia County, leads with 20.5%.[105]

Lancaster County has an unemployment rate of 7.8% as of August 2010. This is a rise from a rate of 7.6% the previous year.[106]

There are 11,000 companies in Lancaster County.[107] The county's largest manufacturing and distributing employers at the end of 2003 were Acme Markets, Alumax Mill Products, Anvil International, Armstrong World Industries, Bollman Hat, CNH Global, Conestoga Wood Specialties, Dart Container, High Industries, Lancaster Laboratories, Pepperidge Farm, R R Donnelley & Sons, The Hershey Company, Tyco Electronics, Tyson Foods, Warner-Lambert, and Yellow Transportation.[108]

Auntie Anne's, Clipper Magazine, Lancaster Farming, MapQuest, Turkey Hill Dairy, Clair Global, and Wilbur Chocolate Company are Lancaster County-based organizations with an economic footprint of regional or national significance.

Herley Industries is a local producer of microwave and millimeter wave products for the defense and aerospace industries.

Agriculture

[edit]With some of the most fertile non-irrigated soil in the U.S., Lancaster County has a strong farming industry.[109][110] Lancaster County's 5293 farms, generating $800 million in food, feed and fiber, are responsible for nearly a fifth of the state's agricultural output.[111] Chester County, with its high-value mushroom farms, is second, with $375 million.[112]

Livestock-raising is responsible for $710 million of that $800 million, with dairy accounting for $266 million, poultry and eggs accounting for $258 million. Cattle and swine each accounts for about $90 million.[111]

Agriculture is likely to remain an important part of Lancaster County: almost exactly half of Lancaster County's land – 320,000 acres (130,000 ha) – is zoned for agriculture, and of those, 276,000 acres (112,000 ha) are "effective agricultural zoning", requiring at least 20 acres (8.1 ha) per residence.[113]

Tourism

[edit]

Tourism is a significant industry in Lancaster County, employing approximately 20,000. In the 1860s, articles in the Atlantic Monthly and Lippincott's Magazine published right after the Civil War, introduced Lancaster County to many readers. However, tourism in Lancaster was nearly non-existent prior to 1955.

A New York Times travel article in 1952 brought 25,000 visitors, but the 1955 Broadway musical Plain and Fancy helped to fan the flames of Amish tourism in the mid-1950s. Shortly thereafter, Adolph Neuber (then-owner of the Willows Restaurant) opened the first tourist attraction in Lancaster County showcasing the Amish culture. Lancaster County tourism tapered off, after the 1974 gas rationing and the Three Mile Island incident led to five years of stagnation.[114]

Local tourism officials viewed it as deus ex machina when Hollywood stepped in to rescue their industry. Harrison Ford, in the 1985 movie Witness, portrayed a Philadelphia detective who journeys to the Amish community to protect an Amish boy who has witnessed a murder in Philadelphia. The detective is attracted to the boy's widowed mother; the movie is less a thriller than a romance about the difficulties faced by an outsider in love with a widow from The Community.[115] The film was nominated for eight Oscars, and won two.[116] However, the real winner was Lancaster County tourism.

Once again, especially after the September 11, 2001 attacks, tourism in Lancaster County has shifted. Instead of families arriving for a three- to four-day stay for a general visit, now tourists arrive for a specific event, whether it be the rhubarb festival, the "maize maze", to see Thomas the Tank Engine, for Sertoma's annual "World's Largest Chicken Barbecue" or for the latest show at Sight & Sound Theatres.[114] The tourism industry is discouraged by this change, but not despondent:

In four years of working here on the Strasburg Rail Road, I've only had one complaint, she said that the ride is too short. People love Lancaster County. They'll keep coming back.

— Betty McCormack[114]

The county promotes tourist visits to the county's numerous historic and picturesque covered bridges by publishing driving tours of the bridges.[117] With over 200 bridges still in existence, Pennsylvania has more covered bridges than anywhere else in the world, and at 29 covered bridges, Lancaster County has the largest share.[118]

The Lancaster County Convention Center Authority [15] constructed the $170 million[119] Lancaster County Convention Center in downtown Lancaster on the site of the former Watt & Shand building.[120]

Other tourist attractions include the American Music Theatre, Dutch Wonderland, Ephrata Cloister, Ephrata Fair, Hans Herr House, Landis Valley Museum, Pennsylvania Dutch Country, Pennsylvania Renaissance Faire (one of the largest Renaissance fairs in the world[121]), Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania, Rock Ford plantation, Robert Fulton Birthplace, Sight & Sound Theatres, Strasburg Railroad, Wilbur Chocolate, Wheatland (James Buchanan House) and Sturgis Pretzel House. There are many tours of this historic area including the Downtown Lancaster Walking Tour.[122]

Education

[edit]Lancaster County's colleges include Eastern Mennonite University, Elizabethtown College, Franklin & Marshall College, Harrisburg Area Community College, Lancaster Bible College, Lancaster Theological Seminary, Millersville University of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania College of Art and Design, Thaddeus Stevens College of Technology, and PA College of Health Sciences.

There are 16 public school districts in the county:[123]

There is also one charter school, the La Academia Charter School. Lancaster Country Day School, an independent day school, is located on the west end of Lancaster City. Linden Hall, an independent boarding and day school for girls, is located in Lititz.

Lancaster County has a federated library system with 14 member libraries, three branches and a bookmobile. The Library System of Lancaster County was established in April 1987 to provide countywide services and cooperative programs for its member libraries. The Board of Lancaster County Commissioners appoints the Library System of Lancaster County's seven-member board of directors. The System is an agent of the Commonwealth.

Sports

[edit]Before the Barnstormers, Lancaster was the home of the Lancaster Red Roses, which played from 1906 to about 1930, and from 1932 to 1961.[124] In 2005 the Lancaster Barnstormers joined the Atlantic League of Professional Baseball. The Barnstormers are named after the "barnstorming" players who played exhibition games in the county. Their official colors are red, navy blue, and khaki, the same as those of the Red Roses. This franchise won their first league championship in their second season, in 2006. They won their second league championship in 2014. They have revived the old baseball rivalry between Lancaster and nearby York, called the War of the Roses, when the York Revolution started their inaugural season in 2007.[125]

The Women's Premier Soccer League expanded to Lancaster for the 2008 season, with the Lancaster Inferno. The WPSL is a FIFA-recognized women's league. The Inferno is owned by the Pennsylvania Classics organization and play their home games at the Hempfield High School stadium in Landisville. The Inferno's colors are orange, black, and white.

Amateur teams

[edit]In 2004, the amateur Lancaster Lightning football team of the North American Football League played at Pequea Valley High School's football stadium in Kinzers.[126]

Lancaster is home to the Dutchland Derby Rollers (DDR), a member of the Women's Flat Track Derby Association (WFTDA.) Founded in 2006, The Dutchland Rollers have two travel teams, the All-Stars and the Blitz. Both rosters play teams from neighboring leagues, though it is the Dutchland All-Stars that compete for national ranking. Their home rink is Overlook Activities Center, and their colors are orange and black.

Former teams

[edit]From 1946 to 1980, a professional basketball team, as the Lancaster Red Roses, (as well as the Lancaster Rockets and the Lancaster Lightning) played in the Continental Basketball Association.[127]

Transportation

[edit]Lying on the natural route from Philadelphia to the western part of Pennsylvania, Lancaster County has given rise to many improvements in transportation, such as the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike, later part of the Lincoln Highway, in 1794,[128] a canal in 1820, and the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad in 1834.[129]

Major roads and highways

[edit]Current railroads

[edit]

As of 2006[update], passenger service in Lancaster County is provided by Amtrak, whose Keystone Corridor passes through the county, with stops at Lancaster, Mount Joy and Elizabethtown. A station is planned at Paradise to provide connecting service with the Strasburg Railroad, which runs passenger excursions from nearby Leaman Place to Strasburg.

The principal freight operator in the county is Norfolk Southern Railway (NS). The NS main line follows the Susquehanna River (with trackage rights for Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR)), and leaves the county by crossing the river on Shocks Mills Bridge near Marietta. NS also has trackage rights over the Keystone Corridor, to which it is connected by the Royalton Branch, which runs north along the river from the main line at Marietta, and the Columbia Branch, which runs from the Corridor at Dillerville to the main line at Columbia. Two other NS branches originate on the Corridor: the Lititz Secondary, which runs from Dillerville to Manheim and ends at Lititz, and the New Holland Industrial, which leaves the Corridor around the east end of Lancaster to run east to New Holland and ends at East Earl.

Several short lines also operate in the county. With the exception of the Strasburg Railroad, all are freight railroads. The East Penn Railroad (ESPN) operates on a spur off the NS branch to Manheim, and on a longer line in the northeast corner of Lancaster County into Berks County. Landisville Terminal and Transfer Company (LNTV) operates on a spur off the Amtrak line at Landisville. The Tyburn Railroad operates some trackage around Dillerville. The Columbia and Reading Railway (CORY) began operating on 2.5 miles (4.0 km) of track in Columbia in January 2010.[130]

Airport

[edit]There are two public airports in Lancaster County. Lancaster Airport has scheduled passenger service, and Smoketown Airport serves general aviation users.

Communities

[edit]

The following cities, boroughs, and townships are located in Lancaster County:

City

[edit]Boroughs

[edit]Christiana is the least populated borough in Lancaster County, as of 2010[update].[131] Columbia is the most populous.

Townships

[edit]- Bart

- Brecknock

- Caernarvon

- Clay

- Colerain

- Conestoga

- Conoy

- Drumore

- Earl

- East Cocalico

- East Donegal

- East Drumore

- East Earl

- East Hempfield

- East Lampeter

- Eden

- Elizabeth

- Ephrata

- Fulton

- Lancaster

- Leacock

- Little Britain

- Manheim

- Manor

- Martic

- Mount Joy

- Paradise

- Penn

- Pequea

- Providence

- Rapho

- Sadsbury

- Salisbury

- Strasburg

- Upper Leacock

- Warwick

- West Cocalico

- West Donegal

- West Earl

- West Hempfield

- West Lampeter

Census-designated places

[edit]Census-designated places are geographical areas designated by the U.S. Census Bureau for the purposes of compiling demographic data. They are not actual jurisdictions under Pennsylvania law.

- Bainbridge

- Bareville

- Bird-in-Hand

- Blue Ball

- Bowmansville

- Brickerville

- Brownstown

- Cambridge (partly in Chester County)

- Churchtown

- Clay

- Conestoga

- East Earl

- Falmouth

- Farmersville

- Fivepointville

- Gap

- Georgetown

- Goodville

- Gordonville

- Hopeland

- Intercourse

- Kirkwood

- Lampeter

- Landisville

- Leola

- Little Britain

- Maytown

- Morgantown (mostly in Berks County)

- Paradise

- Penryn

- Reamstown

- Refton

- Reinholds

- Rheems

- Ronks

- Rothsville

- Salunga

- Schoeneck

- Smoketown

- Soudersburg

- Stevens

- Swartzville

- Wakefield

- Washington Boro

- Willow Street

- Witmer

Unincorporated communities

[edit]Many communities are neither incorporated nor treated as census-designated places.

- Aberdeen[132]

- Anchor[133]

- Bamford[134]

- Bausman

- Bellaire[135]

- Bellemont

- Blainsport

- Buck

- Centerville

- Central Manor

- Cocalico

- Conewago

- Creswell

- Dillerville

- Donerville

- Elm

- Farmersville

- Fertility

- Georgetown

- Gordonville

- Hempfield

- Hinkletown

- Holtwood

- Kinzers

- Kissel Hill

- Lyndon

- Martindale

- Mastersonville

- Mechanics Grove

- Mechanicsville

- Narvon

- Neffsville

- New Danville

- New Milltown

- New Providence

- Nickel Mines

- Ninepoints

- Peach Bottom

- Pequea

- Rohrerstown

- Safe Harbor

- Silver Spring

- Smoketown

- Talmage

- Vintage

- White Horse

Population ranking

[edit]The population ranking of the following table is based on the 2010 census of Lancaster County.[136]

† county seat:

| Rank | City/Town/etc. | Municipal type | Population (2010 Census) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | † Lancaster | City | 59,322 |

| 2 | Ephrata | Borough | 13,394 |

| 3 | Elizabethtown | Borough | 11,545 |

| 4 | Columbia | Borough | 10,400 |

| 5 | Lititz | Borough | 9,369 |

| 6 | Millersville | Borough | 8,168 |

| 7 | Willow Street | CDP | 7,578 |

| 8 | Mount Joy | Borough | 7,410 |

| 9 | Leola | CDP | 7,214 |

| 10 | New Holland | Borough | 5,378 |

| 11 | Manheim | Borough | 4,858 |

| 12 | East Petersburg | Borough | 4,506 |

| 13 | Akron | Borough | 3,876 |

| 14 | Denver | Borough | 3,861 |

| 15 | Maytown | CDP | 3,824 |

| 16 | Reamstown | CDP | 3,361 |

| 17 | Rothsville | CDP | 3,044 |

| 18 | Brownstown | CDP | 2,816 |

| 19 | Strasburg | Borough | 2,809 |

| 20 | Mountville | Borough | 2,802 |

| 21 | Salunga | CDP | 2,695 |

| 22 | Marietta | Borough | 2,588 |

| 23 | Quarryville | Borough | 2,576 |

| 24 | Swartzville | CDP | 2,283 |

| 25 | Bowmansville | CDP | 2,077 |

| 26 | Gap | CDP | 1,931 |

| 27 | Landisville | CDP | 1,893 |

| 28 | Reinholds | CDP | 1,803 |

| 29 | Adamstown (partially in Berks County) | Borough | 1,789 |

| 30 | Lampeter | CDP | 1,669 |

| 31 | Rheems | CDP | 1,598 |

| 32 | Clay | CDP | 1,559 |

| 33 | Bainbridge | CDP | 1,355 |

| 34 | Brickerville | CDP | 1,309 |

| 35 | Terre Hill | Borough | 1,295 |

| 36 | Intercourse | CDP | 1,274 |

| 37 | Conestoga | CDP | 1,258 |

| 38 | Christiana | Borough | 1,168 |

| 39 | Fivepointville | CDP | 1,156 |

| 40 | East Earl | CDP | 1,144 |

| 41 | Paradise | CDP | 1,129 |

| 42 | Schoeneck | CDP | 1,056 |

| 43 | Blue Ball | CDP | 1,031 |

| 44 | Penryn | CDP | 1,024 |

| 45 | Georgetown | CDP | 1,022 |

| 46 | Farmersville | CDP | 991 |

| 47 | Morgantown (mostly in Berks County) | CDP | 826 |

| 48 | Hopeland | CDP | 738 |

| 49 | Washington Boro | CDP | 729 |

| 50 | Stevens | CDP | 612 |

| 51 | Wakefield | CDP | 609 |

| 52 | Soudersburg | CDP | 540 |

| 53 | Gordonville | CDP | 508 |

| 54 | Witmer | CDP | 492 |

| 55 | Goodville | CDP | 482 |

| 56 | Churchtown | CDP | 470 |

| 57 | Falmouth | CDP | 420 |

| 58 | Bird-in-Hand | CDP | 402 |

| 59 | Kirkwood | CDP | 396 |

| 60 | Little Britain | CDP | 372 |

| 61 | Ronks | CDP | 362 |

| 62 | Smoketown | CDP | 357 |

| 63 | Refton | CDP | 298 |

In popular culture

[edit]- The 1985 film Witness took place partially in Lancaster County, where a Philadelphia police officer protects an Amish boy who witnessed a murder while in the City of Brotherly Love.[137]

- The 1997 film For Richer or Poorer involved a wealthy NYC couple, who take refuge in Lancaster County after being framed for tax fraud.[138]

- The 2010 TV movie Amish Grace was a dramatization of the 2006 murders of Amish school children in Nickel Mines.[139]

- Amish Mafia was a reality TV show on the Discovery Channel about a group of Amish men in Lancaster County who protect and keep the peace after the 2006 Nickel Mines murders. The series ran from 2012-2015.[140]

- The 2013 film Are You Here was set in Lancaster County, where the protagonists grew up.[141]

See also

[edit]- List of Lancaster County covered bridges

- List of Pennsylvania films and television shows

- List of people from Lancaster County, Pennsylvania

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania

- Red Rose Transit Authority

References

[edit]- ^ Includes Lancaster, York, Berks, Dauphin, Cumberland, Franklin, Lebanon, Adams and Perry Counties

- ^ "QuickFacts: Lancaster County, Pennsylvania". Census.gov. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- ^ a b 2020 Population and Housing State Data | Pennsylvania

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ Introduction Archived December 8, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Xroads.virginia.edu. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ lancaster, pa. Web.archive.org (March 11, 2007; retrieved December 23, 2010.)

- ^ THE PENNSYLVANIA LEFEVRES. History and Genealogy Book accessed May 31, 2009

- ^ "Historical papers and addresses of the Lancaster County Historical Society" County Historical Society pages 101–124. pub 1917

- ^ The Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History and Diplomacy Archived April 5, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Yale.edu. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ "County".[permanent dead link]

- ^ Martic Township. Horseshoe.cc. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ a b "Counties of Pennsylvania". Pennsylvania State Archives. Archived from the original (Index of 67 Pennsylvania County Histories) on March 6, 2009. Retrieved October 4, 2006.

- ^ Petition for the Establishment of Lancaster County Archived August 7, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, 6 February 1728/9

- ^ A Brief History of Lancaster County. Web.archive.org (February 3, 1999; retrieved December 23, 2010.)

- ^ Brinton, Daniel G., C.F. Denke, and Albert Anthony. A Lenâpé – English Dictionary. Biblio Bazaar, 2009. ISBN 978-1103149223, pp. 81, 85, 132.

- ^ Zeisberger, David. Indian Dictionary: English, German, Iroquois—The Onondaga and Algonquin—The Delaware, Harvard University Press, 1887. ISBN 1104253518, p. 161. The Conestoga never developed a writing system for their language; by 1700 they were defeated and absorbed by larger tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy. Their language is close to that of the Onondaga people of the Iroquois. They are believed to have migrated south from the Great Lakes region centuries before, as did the Cherokee, who occupied areas further to the South.

- ^ Zeisberger (1887), Indian Dictionary, pp. 48, 222

- ^ "Recollections written in 1830 of life in Lancaster County 1726–1782 and a History of settlement at Wright's Ferry, on Susquehanna River" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 30, 2011. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ Hindle, Brooke (October 1946). "The March of the Paxton Boys". William and Mary Quarterly. 3rd. 3 (4): 461–486. doi:10.2307/1921899. JSTOR 1921899.

- ^ The Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History and Diplomacy Archived March 5, 2005, at the Wayback Machine. Yale.edu. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ a b CECIL COUNTY MARYLAND: Where Our Mothers and Fathers Lie Buried. Freepages.history.rootsweb.com. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ Lancaster County Townships Archived October 18, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Pa-roots.com. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ Lancaster County Historical Society. Web.archive.org (January 5, 2008; retrieved December 23, 2010.)

- ^ James Buchanan | The White House. Whitehouse.gov (December 17, 2010; retrieved December 23, 2010.)

- ^ Welcome to LancasterHistory.org Archived August 20, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Wheatland.org. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ STEVENS, Thaddeus – Biographical Information. Bioguide.congress.gov. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ "Pathfinder on Thaddeus Stevens". December 10, 2004. Archived from the original on December 10, 2004. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ see File:Thad Stevens grave.JPG and File:Buchanan grave.JPG

- ^ Introduction Archived November 7, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Millersville University. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ "Slavery in Pennsylvania", Slavery in the North website. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ Turner, Edward Raymond (1911). The Negro in Pennsylvania: Slavery—servitude—freedom, 1639–1861. American historical association. p. 238.

- ^ pilpath Archived July 1, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Muweb.millersville.edu. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ Clayborne Carson, Emma J. Lapsanskey-Werner, Gary B. Nash, The Struggle for Freedom: A History of African Americans, Volume 1 to 1877 (Prentice Hall 2011), p. 206.

- ^ "Christiana Treason Trial (1851)". housedivided.dickinson.edu. Retrieved June 8, 2022.

- ^ "Description of Treason at Christiana: September 11, 1851 by L.D. "Bud" Rettew based on contemporaneous news clippings". Masthof.com. Archived from the original on October 11, 2011. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ Hans Herr House – Lancaster, PA – Hans Herr House Museum Archived August 15, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Hansherr.org. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ By Location[usurped]. Adherents.com. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ News| Mennonite Central Committee Archived August 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Mcc.org. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ "MCC Service Opportunity: Canner Operator #1" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 28, 2014. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ^ "Lititz PA". Linden Hall. July 28, 2007. Archived from the original on October 2, 2011. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ 1767 Isaac Long Barn Archived August 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Mcusa-archives.org (June 16, 1960; retrieved December 23, 2010.)

- ^ "www.topozone.com showing Oregon, Pennsylvania". Topozone.com. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ History: Our Story – UMC.org. Archives.umc.org (April 23, 1968; retrieved December 23, 2010.)

- ^ Congregation Shaarai Shomayim Archived December 31, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Shaarai.org. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ Fraktur Archived August 13, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Antiquesandthearts.com. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ Hamilton Electric Watch History Archived November 4, 2005, at the Wayback Machine. Thewatchguy.com (January 3, 1957; retrieved December 23, 2010.)

- ^ Story of the Pennsylvania Rifle. Ourancestry.com. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ [1] Archived October 22, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ History of Westmoreland County, Volume 1, Chapter 18 Archived May 5, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Pa-roots.com. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ Amish Loft Quilts Archived August 19, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Amishloft.com. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Lancaster 2NE FLTR PLT, PA". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ "Susquehanna River Basin Commission: A water management agency serving the Susquehanna River Watershed". Srbc.net. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ [2] Archived October 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Susquehannock State Park". Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Archived from the original on February 12, 2004. Retrieved September 16, 2006.

- ^ "History of the Valley Forge State Forest". Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Archived from the original on September 1, 2006. Retrieved September 16, 2006.

- ^ "HuntingPA.com Game Lands: Pennsylvania State Game Lands, their general location and acreage". Archived from the original (Searchable Database) on October 6, 2006. Retrieved September 16, 2006.

- ^ The Nature Conservancy in Pennsylvania – New Texas Serpentine Barrens Archived July 16, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Nature.org (October 22, 2010; retrieved December 23, 2010.)

- ^ "Rock Springs Nature Preserve" Archived February 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Lancaster County Conservancy Website, Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ Lancaster Farmland Trust Archived May 24, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Lancaster Farmland Trust (November 13, 1985; retrieved July 23, 2013.)

- ^ "Minor Earthquake Felt Throughout Susquehanna Valley – Pennsylvania News Story – WGAL The Susquehanna Valley". Wgal.com. December 27, 2008. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved July 22, 2010.

- ^ Crable, Ad (September 8, 2009). "Big threat to a little turtle". Intelligencer Journal. Archived from the original on January 27, 2013. Retrieved September 15, 2009.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 24, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ^ a b U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts for Lancaster County. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ^ "MLA Data Center". Mla.org. July 17, 2007. Archived from the original on May 22, 2011. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Lancaster County, Pennsylvania".

- ^ The 12 Largest Amish Communities (2017). at Amish America

- ^ "The Amish Population in 2021". Elizabethtown College, the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies. August 12, 2021. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ Amish Population in the United States by State and County, 2021

- ^ "Amish population grows by 1,000 a year, despite Lancaster County's urban sprawl, development". Lancaster Online. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ Donald B. Kraybill and Nelson Hostetter: Anabaptist World USA, 2001, Scottdale, PA, and Waterloo, ON, pp. 272, 276.

- ^ Dialects of English. Webspace.ship.edu. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ "OMB Bulletin No. 13-01: Revised Delineations of Metropolitan Statistical Areas, Micropolitan Statistical Areas, and Combined Statistical Areas, and Guidance on Uses of the Delineations of These Areas" (PDF). Office of Management and Budget. February 28, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2013 – via National Archives.

- ^ "Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Population of Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". 2012 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. March 2013. Archived from the original (CSV) on April 1, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- ^ "Table 2. Annual Estimates of the Population of Combined Statistical Areas: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". 2012 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. March 2013. Archived from the original (CSV) on May 17, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- ^ Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org.

- ^ The leading "other" candidate, Progressive Theodore Roosevelt, received 12,031 votes, while Socialist candidate Eugene Debs received 687 votes, Prohibition candidate Eugene Chafin received 310 votes, and Socialist Labor candidate Arthur Reimer received 12 votes.

- ^ a b c d Pidgeon, Dave (September 26, 2008). "Democrats celebrate registration gains:Numbers here top 100,000 for 1st time". Intelligencer Journal. Archived from the original on January 27, 2013. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- ^ "Lancaster Dems Announce 100,000th Registration". Solanco News. September 30, 2008. Archived from the original on June 4, 2015. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- ^ "Presidential election of 1856 – Map by counties". geoelections.free.fr.

- ^ Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Department of State. "September 2022 Voter Registration Statistics" (XLS). Retrieved September 21, 2023.

- ^ The Pennsylvania Senate – Senators Listed Alphabetically. Legis.state.pa.us. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ^ The Pennsylvania House of Representatives – Representatives Listed Alphabetically. Legis.state.pa.us. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ^ [3] Archived January 12, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Co.lancaster.pa.us. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ^ "Republican Chris Leppler wins election to replace former Lancaster County Sheriff Mark Reese". November 7, 2017.

- ^ [4] Archived February 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ^ [5] Archived February 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Co.lancaster.pa.us. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ^ [6] Archived January 17, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Co.lancaster.pa.us. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ^ [7] Archived January 22, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Co.lancaster.pa.us. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ^ [8] Archived January 12, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Co.lancaster.pa.us. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ^ [9] Archived January 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ^ [10] Archived January 12, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Co.lancaster.pa.us. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ^ [11] Archived January 26, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Co.lancaster.pa.us. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ^ [12] Archived January 2, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Co.lancaster.pa.us. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ^ "Economic Profile for Lancaster". Bureau of Economic Analysis BEARFACTS. November 16, 2022. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ American FactFinder, United States Census Bureau. "GCT2404. Percent of Civilian Employed Population 16 Years and Over in the Manufacturing Industry: 2005". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ American FactFinder, United States Census Bureau. "GCT2405. Percent of Civilian Employed Population 16 Years and Over in the Information Industry: 2005". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ American FactFinder, United States Census Bureau. "GCT2401. Percent of Civilian Employed Population 16 Years and Over in Management, Business, and Financial Occupations: 2005". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ American FactFinder, United States Census Bureau. "GCT2402. Percent of Civilian Employed Population 16 Years and Over in Professional and Related Occupations: 2005". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ American FactFinder, United States Census Bureau. "GCT2403. Percent of Civilian Employed Population 16 Years and Over in Service Occupations: 2005". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ Unemployment Rates by County in Pennsylvania. Bls.gov (December 10, 2010; retrieved December 23, 2010.)

- ^ [13] Archived January 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Economic Development Corporation: Top Employers Archived October 2, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Watershed Restoration Action Strategy Archived November 6, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Dep.state.pa.us. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ "Agricultural Preserve Board" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 8, 2011. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ a b 2002 NASS Agricultural Census Archived April 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pennsylvania Fact Sheet: PA agriculture income population food education employment unemployment federal funds farms top commodities exports counties financial indicators poverty farm income Rural Nonmetro Urban Metropolitan America USDA organic Census of Agriculture Archived August 31, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Ers.usda.gov (December 16, 2010; retrieved December 23, 2010.)

- ^ "Program Guidelines" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 8, 2011. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ a b c James Buescher (September 5, 2005). "Lancaster New Era (Lancaster, Pa.)". Archived from the original on March 27, 2006.

- ^ "Witness". February 8, 1985 – via www.imdb.com.

- ^ "Witness" – via www.imdb.com.

- ^ "The Covered Bridges of Lancaster County". Lancaster County, PA Government Portal. December 10, 2001. Archived from the original on June 8, 2011. Retrieved September 26, 2006.

- ^ "Covered Bridges". Pennsylvania Dutch Country Welcome Center. Action Video, Inc. 2005. Archived from the original on September 28, 2006. Retrieved September 26, 2006.

- ^ Working together for the future of Lancaster Archived June 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Lancaster First. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ Lancaster County IT and Budget Services. "Lancaster County Website". Co.lancaster.pa.us. Archived from the original on June 20, 2010. Retrieved July 22, 2010.

- ^ De Groot, Jerome (2008). Consuming History. Taylor & Francis. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-415-39945-6.

- ^ "Historic Lancaster Walking Tour | Pennsylvania Dutch Country Activities | Lancaster, PA". Padutchcountry.com. Archived from the original on January 1, 2010. Retrieved July 22, 2010.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Berks County, PA" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 20, 2022. - Text list

- ^ [14] Archived February 4, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ York, PA Baseball Archived July 15, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. York Revolution (August 28, 2007; retrieved December 23, 2010.)

- ^ Lancaster Lightning Archived October 4, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved September 30, 2006.

- ^ Lancaster Red Roses Basketball Archived April 30, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved October 1, 2006.

- ^ "The Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike Road". DOT Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved May 29, 2006.

- ^ Baer, Christopher T. "A General Chronology of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company Predecessors and Successors and its Historical Context". Archived from the original on September 7, 2006. Retrieved September 17, 2006.

- ^ "Pennsylvania Department of Transportation 2010 Railroad Map of Pennsylvania (shows owners and operators)" (PDF). Retrieved May 3, 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Wolf, Paula (March 28, 2010). "Terre Hill tops early Census returns". Intelligencer Journal. Archived from the original on January 3, 2013. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- ^ Aberdeen PA (Google Maps, accessed 24 September 2020)

- ^ Anchor, Mt Joy Township PA (Google Maps, accessed 24 September 2020)

- ^ Bamford PA (Google Maps, accessed 24 September 2020)

- ^ Bellaire PA (Google Maps, accessed 24 September 2020)

- ^ 2010 Census

- ^ Nark, Jason (June 13, 2019). "On Saturday, 'Experience' the Lancaster County Farm Where Harrison Ford's Witness Was Filmed". inquirer.com (The Philadelphia Inquirer). Interstate General Media. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "For Richer or Poorer Movie Review". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ DeJesus, Ivey (March 7, 2010). "'Amish Grace' movie fictionalizes Nickel Mines tragedy, generates debate". pennlive.com. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ George, David (December 13, 2012). ""Amish Mafia": Is there really such a thing as an Amish thug?". Salon.com. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ Puig, Claudia. "You may not want to be there for 'Are You Here'". USAToday.com. Gannett Satellite Information Network. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Daniels, Tom, and Lauren Payne-Riley. "Preserving large farming landscapes: The case of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania." Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 7.3 (2017): 67-81. [16]

- Donnermeyer, Joseph F. "A Demographic Profile of the Greater Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, Amish." The Journal of Plain Anabaptist Communities 3.2 (2023): 1-34. online

- Ellis, Franklin, and Samuel Evans. History of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania: With biographical sketches of many of its pioneers and prominent men (Closson Press, 1883) online

- Henderson, Rodger C. "Demographic patterns and family structure in eighteenth-century Lancaster County, Pennsylvania." Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 114.3 (1990): 349-383. online

- HENDERSON, RODGER CRAIGE. "COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT AND THE REVOLUTIONARY TRANSITION IN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY LANCASTER COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA" (PhD dissertation, State University of New York at Binghamton; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1983. 8309094).

- Klein, Frederic Shriver. Lancaster County Since 1841 (Lancaster County National Bank, 1955).

- Kollmorgen, Walter M. "The agricultural stability of the old order Amish and old order Mennonites of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania." American Journal of Sociology 49.3 (1943): 233-241. online

- Kollmorgen, Walter Martin. Culture of a contemporary rural community: the Old Order Amish of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania (US Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Agricultural Economics, 1942) online.

- Kriebel, Howard Wiegner. "Seeing Lancaster county from a trolley window." (1910). online

- Kurland, Nancy B., and Sara Jane McCaffrey. "Community socioemotional wealth: Preservation, succession, and farming in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania." Family Business Review 33.3 (2020): 244-264. online

- Lawrence, Adam B. "Perceptions of Quality of Life in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania May 2012." (2012). online

- Lord, Arthur C. The pre-revolutionary agriculture of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania (Lancaster County Historical Society, 1975) online.

- McMurry, Sally. Pennsylvania Farming: A History in Landscapes (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2017) see "Chapter 5 Transformations on the Lancaster Plain: The Rise of America’s 'Banner County'" pp.62–78.

- Magee, Erin. " 'Unbecoming and Unfemale a Part': Womanhood and Its Forgotten Role in Shaping the New Republic in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania" (PhD dissertation, Millersville University, 2021). online

- Mombert, Jacob Isidor. An Authentic History of Lancaster County (2020) [17].

- Schneider, David. Foundations in a Fertile Soil: Farming and Farm Buildings in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. (Historic Preservation Trust of Lancaster County, 1994)

- Walbert, David James. "Garden spot: Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, the Old Order Amish, and the selling of rural America" (PhD dissertation, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2000. 9968690).

- WITTLINGER, CARLTON O. "EARLY MANUFACTURING IN LANCASTER COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA, 1710-1840" (PhD dissertation, University of Pennsylvania ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1953. 0004959).

- Wokeck, Marianne. "Cultural Persistence and Adaptation: The Germans of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1729-76." Business and Economic History (1978): 113-127. online